Author: Bill Ward

The Recent Discovery

May 10, 2004 was a big day for me… or I should say, a big-red day. On that day, Patty Leslie Pasztor and I kayaked through limestone canyons on Cibolo Creek a couple of miles southeast of Boerne. We wanted to compile data on the native vegetation of that undeveloped corridor, because it was then in danger of being compromised by highway construction.

Almost as soon as we started paddling down the creek, we were impressed by the abundance of canyon mockorange (Philadelphus ernestii) hanging in full bloom from the canyon walls. We also spotted a number of sycamore-leaf snowbell (Styrax platanifolius) and scarlet penstemon (Penstemon triflorus). Already we knew the Cibolo canyons had vegetation well worth protecting.

Then, as we came around a bend, sharp-eyed Patty spotted some rosettes of big red sage (Salvia pentstemonoides) sprouting out of a steep limestone cliff. Wow! She had just discovered an unknown population of big red sage! I was very happy to be present at that discovery, and I would have been even more impressed if I had realized we had just come upon the largest known extant population of Salvia pentstemonoides!

At the time, I did know that big red sage had a certain celebrity for being “rediscovered” after it was thought to be extinct. Also I was aware that wild populations of big red sage are found in very few sites in the Texas Hill Country and no where else on earth. But if Patty had just discovered a new population in 2004, were there likely to be other stands of big red sage hidden away in unknown sites? Where? I wanted to know more.

The History

I soon learned that the go-to person for information on big red sage is Jackie Poole of Texas Parks and Wildlife. She has been monitoring the known populations of big red sage for many years. Jackie was kind enough to send me copies of her thick files on Salvia penstemonoides (now changed to the original spelling S. pentstemonides). In addition, articles in old Native Plant Society of Texas newsletters were a good source of information about the big red salvia.

The March/April 1985 issue of the NPSOT Newsletter included an article by Manuel Flores describing the rarity, if not extinction, of Salvia pentstemonoides and pleading with readers to report any plants they might find to Geyata Ajilvsgi. Flores listed the few occurrences of big red sage documented since it was first collected by Ferdinand Lindheimer in June 1849. He wrote that Lindheimer collected the first specimens at a place called Comanche Springs, thought to be near the headwaters of Salado Creek in far northern Bexar County.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife data base had the collection site at the Comanche Springs just northwest of Boerne, Kendall County. Either location excited me, because both are near where I live. Maybe there were more populations of big red sage right under my nose!

The “Comanche Springs” in question most certainly was in Bexar County. Accounts in the books “John O. Meusebach: German colonizer in Texas” and “A Life Among the Texas Flora” reveals that Lindheimer was the guest of John Meusebach during 1849, when the founder of Fredericksburg lived at a site called Comanche Spring. A 1978 University of Texas at San Antonio archeological report on Fort Sam Houston property shows that Meusebach built a house near Comanche Spring on land he purchased in 1847. This large tract of land is now part of Camp Bullis in the upper valley of Salado Creek north of San Antonio.

The Texas A&M Bioinformatics Working Group reports that the Salvia pentstemonoides specimens in the Missouri Botanical Garden herbarium include four collected by Lindheimer in 1849. Missouri Botanical Garden labels on these say “San Antonio” and “Comanche Braunfels, etc.”, and one has a location label of “Cibolo.” The Texas A&M Bioinformatics Working Group attributes the “Cibolo” specimen to the town of Cibolo, Guadalupe County, but the geology there is quite different than it is at the presently known stands of big red sage.

To reach Comanche Spring from where Lindheimer lived in New Braunfels, it was necessary to cross Cibolo Creek, and upper reaches of Cibolo Creek are only four miles north of the Meusebach homesite. That might explain why one of the herbarium specimens is labeled “Cibolo.” In his letters to George Engelmann at the Missouri Botanical Gardens, Lindheimer often used “Cibolo” to mean Cibolo Creek. It seems probable that all the 1849 specimens were collected in northern Bexar County, southwestern Comal County, or southeastern Kendall County. This makes me wonder if Lindheimer even might have wandered a few miles up Cibolo Creek and collected some of his 1849 specimens at our “new” site in Cibolo Creek canyon.

Other herbarium specimens preserved at the Missouri Botanical Garden were collected from Kerr County in 1894 and 1943; Gillespie County about 1897; Wilson County in 1879; and Kendall County in 1916, 1940, and 1941. At one time big red sage possibly ranged over a ten-county area centered by Kendall County.

Five years before Manuel Flores wrote the NPSOT News article asking members to be on the lookout for big red sage, Marshall Enquist had identified this salvia up a canyon in Bandera County. Those were the only Salvia pentstemonoides that Enquist found, and he did not include this species in his book “Wildflowers of the Texas Hill Country.”

In the November/December 1987 NPSOT News, Enquist wrote an entertaining account of his pursuit of big red salvia. After his book was published in 1987, he still wanted to add big red sage to his photo collection. To avoid a long trip to the field, he called Patty Leslie (now Pasztor) at the San Antonio Botanical Center to see if he could photograph some in her collection. She laughed and told him the Center had none, because Salvia pentstemonoides probably was extinct, and the last known specimens were seen in 1946 in Verde Creek south of Kerrville.

During the spring of 1987, Enquist, with Patty Leslie and other botanists, revisited the Bandera County canyon to verify that Salvia pentstemonoides indeed still existed. They found a dozen plants of the “long-lost” big red sage at three sites in that canyon.

Meanwhile, Dan Hosage, owner of Madrone Nursery near San Marcos, had found a population of big red sage in Frederick Creek at Boerne in 1986. This may be the same site where E. J. Palmer collected Salvia pentstemonoides in “Upper Cebelo Creek near Boerne” in 1916.

This population contained hundreds of plants. Hosage gathered seed, and his nursery was the first to offer big red sage for sale. Within a few years, seeds from the Kendall County population were passed among lovers of native plants, and Salvia pentstemonoides was widely raised in botanical centers and private gardens. In 1988 Marshall Enquist discovered another Kendall County population of big red sage on a bluff along Big Joshua Creek.

The Mystery

As I read all the reports on big red sage, something started to bother me. The literature either stated or implied that the first specimens of Salvia pentstemonoides were collected by Ferdinand Lindheimer during June 1849 at or near Comanche Spring(s). However, Salvia pentstemonoides was described and named in Germany in 1848 by Kunth and Bouche from material sent to them from the Missouri Botanical Garden by George Engelmann. These dates made no sense to me. If Lindheimer first collected big red sage in 1849, how could the species have been named the year before?

In addition to that, the Texas A&M Bioinformatics Working Group reported that for one of the 1849 herbarium specimens, the “determination of S. penstemonoides is in Lindheimer’s own hand.” If he knew its name in 1849, these were not the first specimens collected. Lindheimer or someone else had to have collected big red sage before 1848.

I told some botanist friends about my quandary. They gave me sympathy, but no answers. In fairness to Jackie Poole, she did pursue the question and solved the “mystery” about the same time I learned the solution. And I found out later that Texas Nature Conservancy’s Bill Carr knew the answer all the time, but I guess I had failed to ask him.

In the meantime, I wrote to the Missouri Botanical Garden to ask if they had a specimen of Salvia pentstemonoides older than 1848. No reply. About that time, a friend happened to introduced me to Shannon Smith, Emeritus Director of Horticulture for the Missouri Botanical Garden. I told him my perceived paradox about the earliest collection of big red sage.

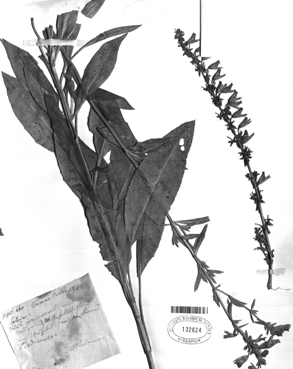

Shannon Smith solicited the help of Douglas Holland, Library Director at Missouri Botanical Garden, and within a day or two the mystery was solved. Mr. Holland found that the herbarium contains a lone specimen of Salvia pentstemonoides collected in 1845. He kindly sent me a scan of the dried specimen with its attached note written by Lindheimer.

Luckily, I have a friend who can read Old German, even that written in the Lindheimer scrawl. Lars Nielsen translated the note to read:

Texas October 1845

Salvia: flowers poppy red (with dark wine-red color) in bunches around riverside bushes on the upper Piedernales (sic).

F. Lindheimer

The 1845 collection date is especially interesting because this was during the period Lindheimer frequently corresponded with Engelmann. Did he mention first finding the plant now known as big red sage in one of those letters? Yes, I think he probably did!

In a letter dated November 20, 1845 (translated in “A Life Among the Texas Flora” by Minetta A. Goyne), Lindheimer describes an October expedition he reluctantly made with Herr von Meusebach to the upper Pedernales River valley. Among the plants he noted was “a delicate Salvia with [illegible word] stemmed leaves and large poinciana-red blossoms.” The plants he shipped to Engelmann from that expedition to the upper Pedernales included the type specimen of Salvia pentstemonoides.

The Present Situation

After Marshall Enquist rediscovered big red sage in the few small populations of the Lost Maples Natural Area of Bandera County, Salvia pentstemonoides also was found in a very small stand on private land in Real County and in the two Kendall County sites already mentioned.

Before the flood of 1997, by far the largest known population of Salvia pentstemonoides flourished on Frederick Creek at Boerne. This probably is the population from which almost all big red sage in cultivation has descended. Prolonged high water in 1997 essentially destroyed most of the salvias here. A dwindling population of rosettes was reduced to four plants by the summer of 2008. Three of those plants had to be rescued from the path of pipeline trenching, and these are being held for re-planting when the site is no longer hazardous. In July 2009, no other plants were found at Frederick Creek.

The Big Joshua Creek population in Kendall County was destroyed years ago, most likely by bank collapse. These Kendall County losses make the 2004 discovery all the more important. The Cibolo Creek population now numbers around 150 plants, and it seems to be in a physically stable setting. This site is now part of the Cibolo Nature Center.

Are there more Salvia pentstemonoides to be found? Probably so! A couple of years ago I was lucky enough to stumble onto a little population of three plants growing out of a steep creek bank on private land in Real County. Last year a nice stand was discovered on a remote canyon wall not far west of Boerne by Frank Kirby and Ronnie Grell. Even during the 2009 drought, there were 107 plants at that site and a few others at other places in that same little canyon.

I’m looking for more!